It’s a 13-hour bus journey from Santiago to Puerto Montt, although the fare for the overnight journey is little more than the cost of a night’s accommodation at the Ibis in Santiago. The Chilean sitting in the next seat has his beady eye on me, as he wants to practise his English. An admirable goal perhaps but less than endearing at 3am. I’m avoiding eye-contact as we roll into another near-identical, cookie-cutter bus station somewhere between Chillan and Temuco; I play dead and he jumps over me to join the driver outside for a cigarette. No food or drink here then! Later on my tummy’s rumbling: I’m wondering if the armrests would be tastier than breakfast I had at the hotel yesterday, but the bus is already pulling into Puerto Montt so there’s no time to find out. I notice a Derek-shaped dent in the super-soft seat as I disembark.

I was in Puerto Montt briefly in 1992, just long enough to change planes on our journey south, missing out on a city tour. Now the town itself looks grey and dismal under grey and dismal skies, so I don’t hang around. Before I leave, I’ll need chocolate and an outdoor shop where I can get tape to plug some of the holes in my tent. But after a fruitless climb to a non-existent shop at the top of a very real hill, I give up and roll out of town along the seafront. Hopefully I’ll find something along the way, and it’s not going to rain anyway, is it? I’m vindicated 10km further down the road at a mini-mall where I feast on empanadas and parcel tape.

The Carretera Austral (Southern Way) is a 1,250km road winding its way south from Puerto Montt to Villa O’Higgins, connecting rural communities previously isolated from the rest of Chile. As there are only 100,000 people living in this coastal region, the investment building and maintaining the road (half of which is paved) is significant. But, while this may not have been in General Pinochet’s mind when he ordered the road to be built in the 1970s, the mountains, forests and lakes draw tourists from around the world to, what is now, one of the top cycling destinations in South America.

I’m thinking about Senor Pinochet’s contribution to my cycling pleasure as I pull into Caleta la Arena, a village where the first of the ferries I’ll need to take leaves. I assume the coastline is, to use the technical term, too “wiggly” to have a road here. A woman with a card machine, slung around her waist like a holster, relieves me of £2.80 and waves me onboard. An Austrian cyclist, coming the other way, looks at the size of my panniers dubiously and wishes me luck. He promises I’ll meet many more cyclists in the coming days, and he’s not wrong.

Later, as I disembark, I spot a sign telling me I’m 55km into my journey. I don’t need a calculator to realise this is two-thirds of diddly squat compared to how far I have to go. To make matters worse, some bright spark has painted the distances on the road too, in increments of 100m. Useful if you want to be constantly reminded how slow you are, but not much else.

At Contao, I knock on doors looking for a room but, even six weeks before Christmas, there’s no room at the inn. I find a campsite and pitch my tent under a tree. I’m sure it’s going to rain and assume the tree will give me some protection. I’m half correct. The following morning I’m rolling up my sleeping pad and looking over my shoulder. One of the owner’s dogs is helping itself to my porridge. Fortunately there’s still some left, so I don’t starve. I’m not proud…

The next two days are wet and I’m testing my Gore-Tex rain-gear: it’s functioning perfectly. There’s no way any of the sweat I am producing on the hills will be getting out from under my raincoat anytime soon. I cast my mind back to the Carretera’s rainfall figures showing November to be one of the driest months here. Maybe I was holding the chart upside down? At the next ferry port, Hornopiren, I check into a hotel to dry my gear. I have to ask twice (and count the toes on both feet) to confirm the hotel really is only £15 a night, including breakfast. How they make money charging those rates is a mystery to me.

The ferry to Caleta Gonzalo is a four-hour journey, but I’m not alone. When I arrive at the port, there are a bunch of cyclists wheeling their bikes down the slipway. As the ship pulls away the rain is merging with the sea, so we spend a happy few hours onboard discussing gear ratios, pannier set-ups and other topics of significance. I’m not the oldest cyclist here and purr appreciatively when described as “much younger” by a 60-something. But for the most part the cyclists are in their late 20s or 30s and have been on the road for one or two years, covering some serious mileage. This is impressive even if I’m not sure two years in the saddle would appeal to me very much.

The following morning the sun comes out and I’m working my way down to Chaiten, a town of around 3,000 people and the biggest place this side of the halfway point at Coyhaique. When I say “down to Chaiten” I mean down, up, down, up, down. This is a constant theme, as the road is usually going up or down, even on the flat. There’s something like 50,000m of ascent and descent overall, although it seems more. Some of this is over passes, but mostly it’s just undulating.

Chicken stew and a slice of apple tart soothe my tired legs before I head out on the (relatively) flat road from Chaiten to Lago Yelcho. Tommaso from Milan has joined me now and a westerly breeze carries us effortlessly to a camping spot 40km down the road. The campsite is part of a lodge that is, frankly, too good for riff-raff like us, but it’s early in the season and we don’t smell too bad, so they allow us inside to drink their over-priced beer before supper.

The next day is nice too, although there’s a bit of a climb up and over to Villa Santa Lucia, where we stock up on snacks. We’re eating a lot of junk food at the moment: I blame Tommaso, he blames me. In the afternoon it clouds over but there’s no rain until the following day. We’re putting in decent miles when the weather’s good and have managed 190km or so over two days by the time we roll into La Junta. As I’d originally only expected to average 60km a day, I’m well ahead of schedule and should be able to work in a rest day later on if I need one.

Our decision not to camp proves to be wise, as we wake up to the sound of “lluvia” drumming on the roof. Tommaso tells me lluvia is the Spanish for rain, so I add this word to my store of 50 Spanish words: it’ll come in useful later. As I’m riding out of town, I point at the sky and shout “lluvia” to a few of the locals, but they don’t seem all that impressed.

It’s a day for a couple of photos and wet feet but little else. We meet a Canadian in Puyuhuapi. He has no tent and a sleeping bag made from ducks with alopecia. He says he sleeps in bus shelters and cycles in sandals. I offer him some of my chips and assure him that tents and warm sleeping bags are overrated. We agree to meet up later and share a muddy culvert, but in the end Tommaso and I stay somewhere dry and warm instead. Having given up my chips, I feel I’ve suffered enough.

The next day the rain is lashing down on us once again. I put plastic bags on my feet, held in place with rubber bands. This provides some protection as my feet are now warm and wet, rather than just wet. I get as much pleasure as I can from the climb over to Villa Amengual, but the rivers look ready to burst their banks and the road is gravel most of the way. It’s a shortish day though, and we’re soon hanging up our gear at the appropriately named Refugio Por Ciclista, where we find our Canadian friend has arrived already, showing no signs of hypothermia.

The pattern repeats itself as we wake up to sunny skies once more. It’s freezing cold when we leave the refuge but the inevitable up, down, up warms the blood and loosens the clothing. The gradients are kind and the fields are full of lupins. The rain is quickly forgotten and the sheer awesome brilliance of riding this road brings energy to the legs and smiles to our faces. Take a large bowl and add some Alpine peaks, mix in Norwegian fjords and waterfalls, add a smattering of Alaskan wildflowers and a dollop of New Zealand remoteness and hey presto! All the ingredients you need to create the magic of this part of Chilean Patagonia.

As we’ve started early (one of the benefits of not camping) and the forecast for the following day is rain once again, we decide to push the full 135km to Coyhaique in one day. There we can bank a day of rest, wash our clothes and relax in the nearest thing to a proper town on this route. It’s a lovely day; the prospect of 1,750m of climbing over 11-hours doesn’t seem as daunting when the peaks are covered with snow and the rivers are twinkling in the sunlight.

We’re now just over halfway after seven days of cycling. This is waaaay further than I’d expected to be. But our tactic of putting in the long days when the sun is shining is paying dividends. If I had longer, I’d probably only cycle on sunny days, but things seem to be working well at the moment and the forecast for the second half is more settled: onwards and downwards!

The southern section has more gravel: one of the reasons for the road being dubbed the “Carretera Dustral”. But at this stage, I’d probably describe it as the Aquaterra Austral or perhaps the Carretera Gustral because of the rain and the wind. Whatever it’s called, the first half at least has to go on any cycle tourist’s bucket list. It’s just awesome… (to be continued)

-

Puerto Montt

-

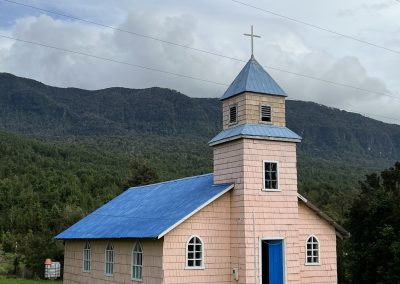

A churchlet

-

Ferry to Caleta Puelche

-

Scene of the Great Breakfast Robbery

-

They do them in pink too!

-

It’s not far, is it?

-

Fanny and Gabriel demonstrate the sheer joy of a hotdog

-

It’s a cappuccino Jim, but not. as we know it

-

Hornopiren at the end of a wet day

-

Here comes the sun, dah dah dah dah…

-

One for the mural collection

-

Cascada Escondida (Hidden Falls)

-

Laguna Negra

-

Big Lights, Big City

-

Why?

-

Chilean Pine

-

Long live the tailwind!

-

Sunbeam

-

Sunbeams?

-

The joy of good weather

-

Lago Yelcho

-

Big skies

-

Embothrium Coccineum (apparently)

-

Churches are also available in white

-

Lunch stop

-

When it’s raining you can always take a photo of an old bridge

-

New park but still a looong way to go

-

Villa Amangual and the only two non-barking dogs in the place

-

Jumping Condor Falls

-

Not far to a nice dry place…

-

Refugio Por Ciclista!

-

Lago las Torres

-

El Capitan?

-

Progress!

-

Lupin time

-

Paramount Pictures presents…

-

No monkeys to be seen

-

Can’t have too many lupin pictures

-

See previous caption

-

“Short-cut” to Coyhaique (mucho gravel)

-

Coyhaique in the distance

-

The nearest I've been to a puma on this trip!