I’ve officially recovered from my previous efforts, thanks to a soothing balm of ice-cream and Stella Artois; it’s time to get back on the road. The broken wire on my odometer has been fixed by a wizard at the motorbike shop, with a pair of pliers, electrical tape and a lighter. ‘No charge senor’ he says, ‘I’m rehearsing for the next J K Rowling movie: “Harry Potter and the Unlikely Bike-Repair Shop in Belen”.’ He points me in the direction of the bus station, apologising that his magic only extends to city limits. Beyond that, he tells me, I’m at the mercy of the coach company Empresa Gutierrez, and their driver who must not be named.

It’s a three-hour journey to Tinogasta (two hours driving and one hour waiting in a place called Salado, for no obvious reason). Tinogasta is Spanish for “barking dogs”, or at least I imagine so, judging by the canine cacophony all night. The breakfast at the guesthouse is excellent though and, as I’m a sucker for coconut sponge cake, all is forgiven. Duly mollified, I set my satnav for Fiambala, 45km along the only road out of town, and test my legs. My legs confirm that three days of ice baths would’ve been better preparation for the hills and headwinds than three days of ice-cream.

Fiambala is an oasis of trees and the last meaningful stop before the Paso San Francisco frontier with Chile. The pass is, as I discover later, still closed despite an announcement in April declaring it open. There’s bad blood still between Argentina and its westerly neighbour, 40 years after the Falklands War. An event marked, in this part of Argentina, with various memorials for soldiers, and slogans featuring the words “British”, “thieving” and “barstewards”, in no particular order. The entrance to Fiambala itself has giant statues of a couple of native-American hunters, like kings of Gondor, to keep the timid at bay. The statue of a condor on the other side of the road, in what looks like a death-flap, is less impressive. Just saying.

I book a room at a place recommended by the tourist office, and negotiate transport to the Balcon de Pissis for the following day. The first person I speak with, called Elbio (Guy Garvey’s love-child?), wants £350 for the 90-km journey, but don’t we all? I explain I only want to go one way, but he’s unimpressed, and promises to get back to me with a lower price when the fires of hell have subsided. The next chap is more reasonable (and less rich) and I’m soon bouncing along the 60km gravel road the Balcon de Pissis shares with a local mine. There are a lot of trucks on the road, making for some interesting overtaking manoeuvres. I point at the Komatsu digger on the low-loader as we go past and ask the driver if the Balcon de Pissis is wonky and in need of repair. He looks at me blankly.

Half an hour later and we’re there. While the other tourists are enjoying what is, wonky or not, a magnificent view, I’m unloading bike, panniers and reserves of willpower before descending 500m to Laguna Negra, where I expect to camp for the night. In a fit of enthusiasm, I cycle round the lake which, even with my sunglasses on, is definitely brown and not black, before taking the Monte Pissis turn, which is helpfully signposted. What isn’t signposted is the Willy-Wonka-style river of chocolate I have to cross before pitching my tent. The river is of unknown depth, and in a hurry to get somewhere but, like Augustus Gloop, I throw caution to the wind and am soon up to my knees, ploughing through. The front panniers are set low and do their best to carry the bike, bags and their owner far downstream, but I hold on tightly, relying on the traction control in my Crocs, until I’m safely on the other side. I make a note to remove the front panniers on the way back.

The following morning I have to cross the river again, but the river has subsided overnight; the water upstream is partially frozen. I prefer hypothermia to drowning, and have crossed to the other side before you can say “I’ve lost all sensation in my feet”. I make a second note to try to avoid having to cross the river at all on the way back by sticking to the right-hand bank – a nice idea, but foiled by matters geographical.

Ten miles of sand and rut later, I’m abandoning my bike and loading the “essentials” into a rucksack. Essentials have grown since Llullaillaco, it would appear, as I struggle to lift the weight onto my back. The food I’m leaving behind is stowed under a pile of rocks, to protect it from any critters crazy enough to live out here. Despite the load, it’s a fairly straightforward walk along a shallow valley with a well-marked path; but it offers little protection from a wind that’s blowing with renewed vigour. After a little over an hour, I stop at a place people have obviously camped before, and spend the next hour and a half trying to put the tent up. It’s an unequal struggle but, as I don’t intend to sleep in the open unless palm trees are involved, I eventually prevail. I discover the secret is to fill the inner tent with rocks first before putting it up. You then secure the outer with a couple of guy ropes. With the right amount of cord you can get the outer over the inner and secure them both before the whole kaboodle gets blown to Buenos Aires. Once inside, if you’re feeling brave, you can start to jettison the rocks.

A bit later, after a delicious, if unoriginal, meal of noodles, soup and coffee, I’m watching lenticular clouds forming over the mountains to the east. This is usually a sign of bad weather, but the forecast from home (Cathy’s sending me text messages via my InReach GPS) is for things to remain settled for the next two days. I take some pictures, but will have to ration these over the next few days, as I’ve had a senior moment and left my charging cable behind with the bike.

The next day’s hike is a bit of a slog. The path follows a dry river valley, first to the left and then over a low rise to the bottom of the glacier on the mountain’s north-east side. All told, it’s an eight mile hike and a 1,100m climb to camp two at 5,750m; still 1,050m short of the peak sitting tantalisingly above me. The summit looks close, but the laws of perspective elude me, as they did during art lessons at school.

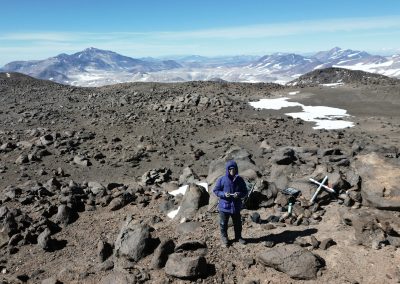

The following morning there’s a bit of a breeze, so I make a good start at 2am. The moon is full-ish but, in the words of the Chinese proverb: all scree looks the same at night. So I don crampons and stick to the snow on the edge of the glacier where the ground is firmer. At 5am I come to a virtual halt, as the snow has run out and the lung-busting scree offers little respite. There’s a snowy ridge, but I don’t like the look of it, so I continue to circumnavigate the mountain looking for kinder slopes. It’s cold and windy, and I’m regretting the early start as navigating would have been easier in the early light. It would have been warmer too. The good news is I’m have no issues with the altitude, and by 9am I’m on a lumpy summit plateau wondering if I’ve climbed the right mountain. But the cross and assorted gubbins I find on the rocky highpoint allay my concerns. I smile winningly for my summit selfie. I’ve brought Dronio all this way and have to give him his moment of glory. But his attempts to capture the epic views are spoiled by strong winds, as he’s thrown hither and thither like a demented dragonfly. I coax him down and catch him at my third attempt. Phew!

On the way down, I decide to take route one and end up on the glacier. This is a bit of a schoolboy error, as I know climbers have disappeared down crevasses on this mountain in the past. As there’s not a lot of snow it’s not too bad finding my way; I do my best to avoid any suspicious cracks and am back at the tent by midday. The glacier may be hazardous, but it’s quick. I lie down in the tent to enjoy the moment, but the angel on my shoulder is telling me to pack up and head down to camp 1. The devil has other ideas, as I’m nice and warm out of the wind. Memories of an uncomfortable second night on Llullaillaco come flooding back and the guy with wings and a harp wins the day. Half an hour later I’m on my way.

I take a slightly different route back to camp one via a different valley, as it looks quicker. Predictably it isn’t, and I’m in penitente heaven for the 3 hours it takes me to get down. But the half hour I lose with my detour is recovered by putting the tent up in double-quick time (using the techniques I learned two days earlier). I’m even-stevens for the day and can enjoy a relatively comfortable night at “only” 4,650m. It also gives me an outside chance of walking, cycling and hitching to Fiambala the following day. If I’m unlucky, it’ll be a three-day ride starting with a 500m climb back up to the Balcon.

It’s a 4km walk back to my bike and I’m half expecting my kit bag to have been gnawed open by something small and furry. But all’s well: the area is rodent-free. I change into “clean” clothes (a relative term), in case I’m lucky enough to get a lift, and cycle back to the river. I arrive shortly after 2pm. Plan A (avoiding crossing altogether) is replaced with Plan B (getting covered in mud in the attempt). I cross over anyway, leaving my Crocs on for the more perilous second part a km further on. Willy Wonka has the taps on full flow; a mid-afternoon bath is looking quite likely. I remove the front panniers and I’m about to plunge in, when I hear the roll of tyres and the toot of a horn behind me. Elbio and a friend have turned up, just in the nick of time, in two vehicles. They obviously don’t fancy my chances and offer me a lift with Diego and Martin, a couple of bemused tourists from Buenos Aires. It’s really the earliest point at which I could possibly have hoped to get a lift and I consider myself extremely fortunate (not for the first time). I’m back in Fiambala by 5pm: result! I celebrate with two triple-scoop ice-creams (I’m nothing if not predictable) and ponder my next step. This turns out to involve a convivial evening of beer and empanadas with Diego and Martin; they’ve been awake since 2am and should know better. Diego is a big Rio Plata FC fan and shows me photos of him wearing his shirt in different places all around the world. That’s dedication!

To summarise this part of the trip: Monte Pissis is the second highest volcano in the world. Or possibly not, as not all sources consider it to be a proper volcano. It’s the third highest mountain in South America, although my unreliable altimeter reading on the summit put it at around sixth. It’s only climbed around five or six times a year, but if it had a more macho name (like Monte Six-Pack or Monte Chris Hemsworth) I’m sure it would get more ascents: who knows? What I can say is that the battle between my desire to climb high mountains in remote areas on the one hand, and my wish to consume ice-cream and beer on the other, is at a tipping point. After four 6,000m peaks, I’ve done most of what I wanted to do in terms of summits: any more would be just, well, greedy. As Paso San Francisco is closed, I won’t be bagging any of the peaks I had my eye on near the border, so it looks as if I’ll be taking a bus south to Mendoza next in any event. There’s a big mountain down there I could take a look at, but it’s early in the season which could make an ascent of Aconcagua, before 1 December, a bit problematic. Let’s see…

-

Belen joins the mural competition

-

If you want crak, this is the place to get it

-

A quality breakfast in Tinogasta

-

Cheap paint is available in certain colours

-

Hands off!

-

Er, welcome to Fiambala?

-

I insist lunch is served by a woman in traditional costume and a condor

-

Balcon de Pissis

-

Region of the 6,000m peaks…

-

…or possibly the 6,000 trucks

-

Flamencos!

-

Laguna Azul

-

The solitude of the vicuna

-

Does anyone have a boat?

-

Lenticular clouds: storms ahead

-

Job done!

-

Dronio did not enjoy the wind

-

Patterns in the snow…

-

Elbio, Diego and Martin (Veronica taking photo)